Documenting Our Hawkers

Early Singapore Food Guides

Singapore’s culinary journey, from its early documentation in colonial travelogues to the rise of today’s influential food blogs, reflects a deep and enduring passion for food. These publications, along with countless other forms of culinary expression, have helped shape and preserve Singapore’s unique food culture, culminating in the prestigious UNESCO recognition of its hawker heritage.

|

| Singapore’s vibrant culinary scene has been thoughtfully chronicled over the decades through travel guides, food directories, cookbooks, and other publications. As early as colonial times, guides like Willis’s Singapore Guide (1936) highlighted popular spots to eat and unwind. For instance, Raffles Place, John Little, and Robinson’s were not only listed as shopping destinations, but also places with lounge cafes offering tea, coffee, ices, and alcoholic beverages in cool and relaxing atmosphere. The guide also spotlighted Oi Mee Hotel at Pasir Panjang for its excellent Chinese dinners and dedicated an entire chapter to the iconic Satai (Satay) Club, then located on Hoi How Road, near Beach Road. Complementing the text were photographs of street hawkers, showcasing a wide array of food offerings, including the much-loved durians. Shown here is the cover of Willis’ Singapore Guide available in NL Online. (Image Credit: All rights reserved. National Library Board) |

|

| The trend of showcasing dining spots across the island continued during the nation-building years, with the Singapore Tourist Association (now the Singapore Tourism Board) actively promoting both restaurant and hawker fare from various ethnic groups to locals and tourists alike in food directories such as Singapore Gourmet’s Guide (RCLOS 642.56 SGG) and later Singapore: Our Gourmet World (RCLOS 642.5095957 SIN) since the 1960s. Other than serving as valuable resources for culinary exploration, these guides also highlighted where to enjoy Chinese, Indian, Malay, Japanese, and European cuisines, while delving into the history of many featured dishes. Shown here is the cover of Singapore: Our Gourmet World available at the National Library Singapore. (Image Credit: All rights reserved. Singapore: Our Gourmet World. Singapore Tourist Promotion Board) |

|

| Alongside the food guides published by the tourism board, private publishers and individuals also produced their own directories and guides from the 1960s through the 1980s. Titles such as Where to Eat and Entertain (RSING 642.5095957 WEES), Good Food Guide to Singapore (RCLOS 642.56 BRU), and Good Food in Singapore (RCLOS 642.50255957 GFS) not only highlighted dining spots and delved into the history of various dishes, but also provided insights into the backgrounds of hawkers and restaurant owners, as well as steps to prepare their signature dishes. Shown here is the 1980 cover of Where to Eat and Entertain available at the National Library Singapore. (Image Credit: All rights reserved. Where to Eat and Entertain. Times Directories) |

|

| The 1980s also witnessed a bold and creative venture with the release of The Secret Food Map of Singapore in 1987. Crafted by Rosalind Mowe, Anne Ropion, and Elyane Hunt as a companion to the The Secret Food Map of Singapore (1987), this food map broke away from the conventional text-and-photograph-based guides of the time. Instead, it presented a vibrant, hand-drawn map-centric guide that located eateries within the physical landscape. A unique colour-coding system was used, with red for Chinese food, green for Malay or Nonya cuisine, black for other Asian fare, and blue for Western dishes. The map showcased a wide range of options, from Vietnamese and Thai eateries to humble hawker stalls offering comfort foods like goreng pisang (deep-fried bananas). Shown here is a food map of Shenton Way taken from The Secret Food Map of Singapore which is available at the National Library Singapore. (Image Credit: All rights reserved. The Secret Food Map of Singapore, 1987. Ropion Hunt Mowe) |

The claim that Singapore is a food paradise is not a recent phenomenon as the country’s unique, multicultural culinary identity was recognised and promoted from its earliest days of independence. A testament to this is Minister Eddie Barker’s 1968 endorsement of Singapore as a food destination in the Singapore Gourmet's Guide. Click or tap HERE to find out what he wrote. (Source: Singapore Gourmet’s Guide)

”Singapore has been described as one of the world’s greatest eating-houses. This description is both amusing and apt having regard to our multi-racial society and the varied culinary arts found here both in their pure, ethic types as well as in their synthesis in the Singapore forms. In air-conditioned restaurants or in open-air places…Singapore offers a variety of food and delicacies, reflecting yet another aspect of our claim to be a fair cross-section of Asia, if not of the world…”

Singapore’s Culinary Tourism Push in the 1990s

In the 1990s, Singapore took a deliberate step to position its diverse culinary landscape as a key tourist attraction. The launch of initiatives like the Singapore Food Festival and the World Gourmet Summit marked a new era in promoting the nation’s rich food heritage to a global audience.

|

| In the 1990s, Singapore began promoting its food as a major attraction for tourists, marked by the launch of the Singapore Food Festival in 1994. Organised annually by the Singapore Tourism Board (STB), this culinary event celebrates Singapore’s rich food heritage and vibrant local culinary scene, highlighting the nation’s favourite cuisines and hawker fare from all ethnic groups. The inaugural festival featured a month-long extravaganza of feasting and entertainment at venues ranging from upscale five-star restaurants to humble hawker centres. Showcasing dishes that spanned local multi-ethnic flavours and international cuisine in multiple locations such as Clarke Quay, Little India, the Malay Village in Geylang, Singapore River (shown above) and Sentosa, and the event was designed to appeal to both visitors and locals alike. (Image Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

The launch of the Singapore Food Festival in 1994 started the trend of packaging Singapore as a food paradise and destination by the Singapore Tourism Board. But what was the festival’s goal? Click HERE to read how then Minister for Trade and Industry Yeo Cheow Tong put it. (Source: The Straits Times)

"The fine food of Singapore is a mouth-watering experience which deserves to be told internationally. For, while Singaporeans never tire of exchanging notes on where the latest good food can be found, the world remains largely unaware of this aspect of our culture…Over this month, the variety and superb quality of Singapore cooking will be on display to the world…The festival should win new converts to our cuisine and strengthen the Lion City’s image a gourmet’s paradise."

|

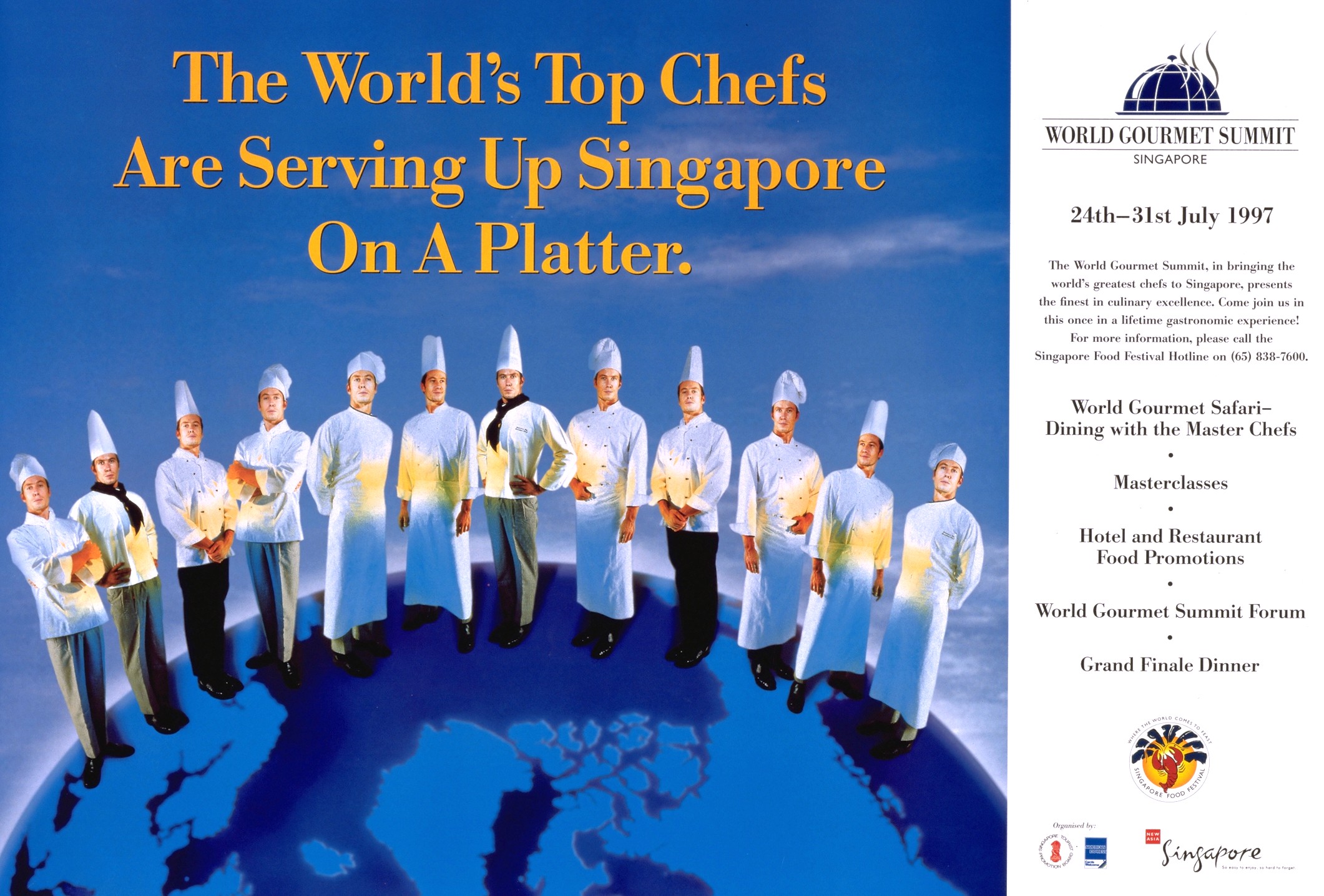

| Besides the Singapore Food Festival, STB also launched the World Gourmet Summit in 1997 in partnership with Peter Knipp Holdings (PKH) as an upscale, Western-centric counterpart to the Singapore Food Festival. Conceived by former STB CEO Tan Chin Nam and food consultant Peter Knipp, the summit showcased the culinary artistry of world-renowned master chefs. The inaugural event featured chefs from 12 prestigious hotels and restaurants, who hosted cooking classes and gourmet safaris, offering lavish four-course meals at premium prices. Shown above is a poster from the 1997 World Gourmet Summit. (Image Credit: Singapore Tourism Board, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| In 2024, to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Singapore Food Festival, the event embraced the theme “A Celebration of Old and New,” departing from its traditional festival village format where food stalls were concentrated in one location (seen above). Dining experiences were paired with entertainment across the island, offering a blend of innovation and tradition. Marquee Singapore showcased futuristic culinary techniques that redefined dining and drinking experiences, while CHIJMES featured a four-course lunch or six-course dinner accompanied by live ballet performances. At Marina Bay Sands, the Food Is Art exhibition presented chocolate sculptures and installations exploring the connection between plants and music. Immersive storytelling was also a highlight, with events like a Chinese tea ceremony paired with dance performances, celebrating the interplay of tradition and modernity. Pop-up events at malls and other locations rounded out the festival with family-friendly showcases and creative bites from top chefs, ensuring a memorable gastronomic experience for all. (Image Credit: Photo by Choo Yut Shing via Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)) |

A Local Food Identity

Singapore’s vibrant food scene isn’t just a government initiative — it is a passion shared by many. Beyond official branding efforts, individuals like K. F. Seetoh and Dr Leslie Tay, among others, championed our unique culinary heritage, creating influential food directories and reviews in the 1990s. Their work ignited a food-focused explosion in the 2000s, paving the way for food bloggers, documentaries, and more. These passionate contributions cemented Singapore’s food legacy and continue to shape our ever-evolving gastronomic story.

|

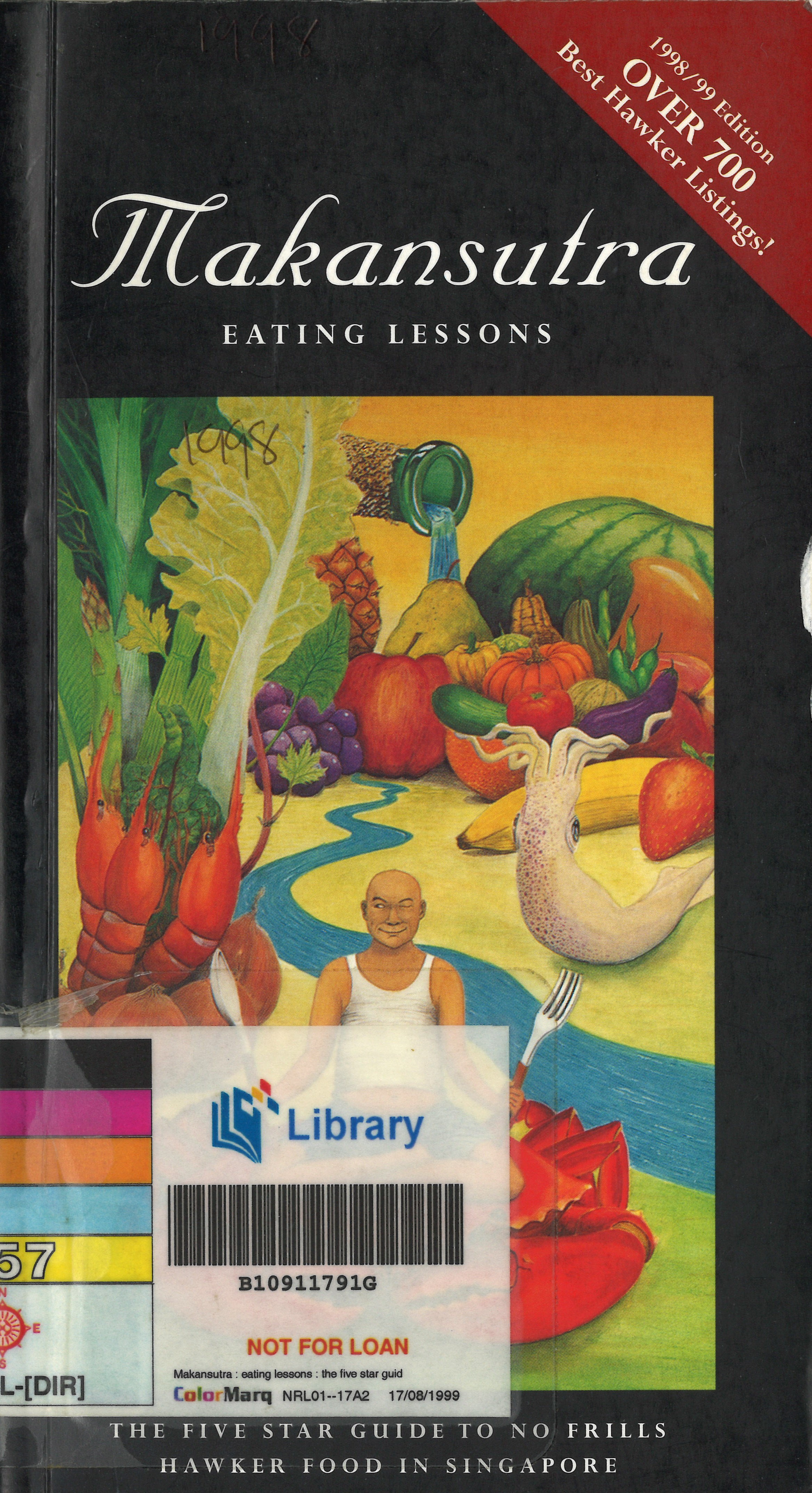

| Created by local food consultant, photographer, writer and television host Seetoh Kok Fye, better known as K. F. Seetoh, the first edition of Makansutra (RSING 647.955957 MEL) was published in 1998 at the cost of S$40,000. It listed selected hawker stalls along with their address and food rating. The guide used a novel chopstick rating system, with more chopsticks indicating a higher rating. The maximum score of three pairs of chopsticks carried the now-famous catchphrase, “Die, die must try!”. Shown above is the cover of the 1998 edition of Makansutra available at the National Library Singapore. (Image Credit: All rights reserved. Makansutra, 1998. Makansutra Pub.) |

|

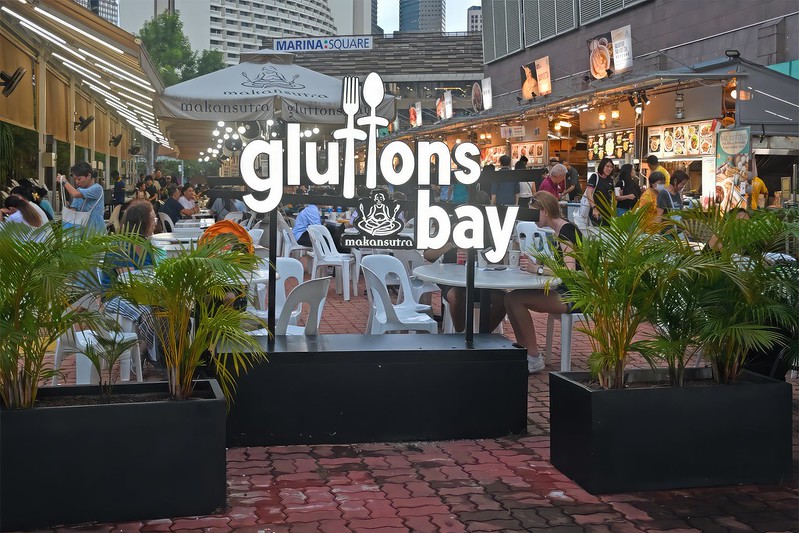

| Over the years, at least nine editions of Makansutra were released, selling an average of 25,000 copies per edition in Singapore, and has expanded to cover other Asian countries. Beyond its popular guidebooks, Makansutra’s influence extends to a website (launched in 1999) featuring articles, videos, a forum, and information on its publications and TV series, as well as a smartphone app for locating and rating nearby eateries. Its television presence, beginning in 2001, includes four seasons featuring KF Seetoh exploring hawker fare, along with spin-off series like “Makansutra Raw” and “Food Surprise!” showcasing both Singaporean and Malaysian cuisine. In addition, Makansutra also opened a food court in the Esplanade known as Glutton’s Bay in 2005 (shown here). (Image Credit: Photo by Choo Yut Shing via Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)) |

|

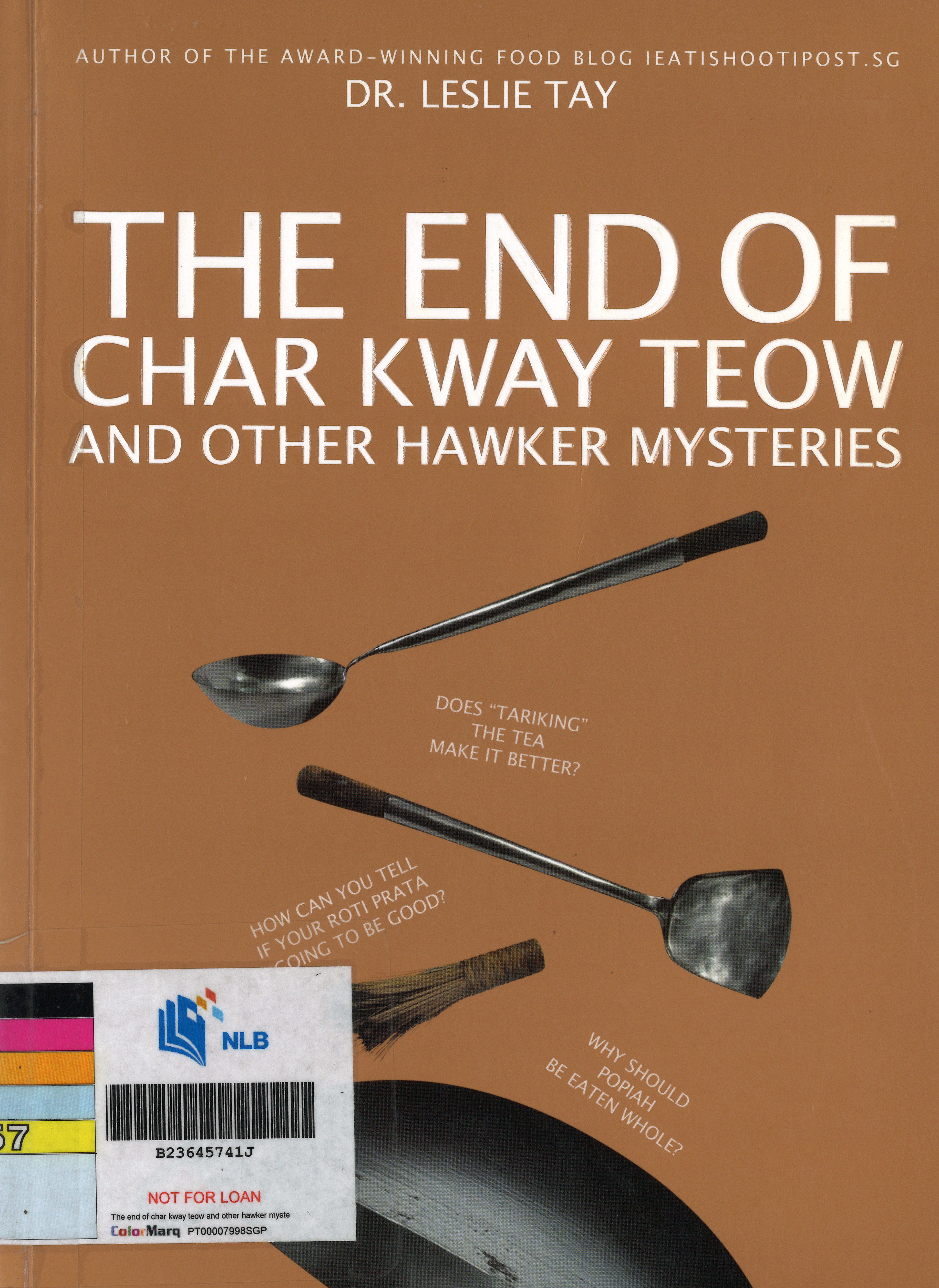

| Following the success of Makansutra, a wave of food-related content emerged, including blogs, websites, publications, and social media videos. A prominent example is Dr. Leslie Tay’s blog, ieatishootipost.sg, launched in 2006, where he documents his two-decade-long quest for Singapore’s best hawker food through photos and stories. His work has earned him recognition in various publications, events and TV programmes, including co-hosting the series “8 Days Eat” and partnering with the World Gourmet Summit for its Hawker Series. Tay has also authored four books on Singaporean cuisine, including the bestsellers Only the Best (2014) (RSING 647.955957 MEL) and The End of Char Kway Teow and Other Hawker Mysteries (2010) (RSING 647.955957 MEL). Shown here is the cover of The End of Char Kway Teow and Other Hawker Mysteries available at the National Library Singapore. (Image Credit: All rights reserved. The End of Char Kway Teow, 2010. Epigram Books)) |

|

| Alongside ieatishootipost, food guide platforms like HungryGoWhere, with its user reviews and curated lists, became essential resources for diners seeking dining options across Singapore. Similarly, in-depth reviews of Singaporean cuisine as well as international fare were also provided by others like MissTiamChiak, LadyIronChef, SethLui.com, Eatbook.sg, The Meat Men and many more. Collectively, these food guides contribute to Singapore’s vibrant food scene, offering diverse perspectives and helping both locals and tourists navigate the country’s dynamic culinary landscape, from hawker centres to restaurants. (Image Credit: Photo by Choo Yut Shing via Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)) |

|

| As Singapore’s food scene evolved, so did the debate over culinary authority. The rise of influential local foodies and food guides demonstrated the growing power of local voices in shaping culinary discourse. This dynamic was further complicated in 2016 when the Michelin Guide’s inaugural Singapore edition (RSING 647.955957 S) ignited controversy, with many criticising the French guide’s perceived lack of understanding of local hawker culture. This division underscored the strong sense of ownership Singaporean foodies feel over their culinary heritage, even when faced with a globally recognised arbiter of taste. Shown here is the cover of the 2016 Singapore edition of The Michelin Guide available at the National Library Singapore. (Image Credit: All rights reserved. The Michelin Guide: Singapore, 2016. Michelin Travel Partner)) |

International Recognition of Singapore’s Hawker Culture

The pinnacle of the evolving hawker scene in Singapore arrived when the country’s hawker culture was successfully inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity on 16 Dec 2020. This coveted recognition marked the culmination of decades of efforts undertaken by the nation in preserving its hawker culture, solidifying it as a vital and celebrated aspect of Singaporean identity.

|

| The journey towards UNESCO recognition for Singapore’s hawker culture began long before the official nomination. For decades, hawker centres had been serving as vibrant community hubs, nourishing not just stomachs but also social bonds. Organisations like the National Heritage Board (NHB) began documenting and celebrating this unique aspect of Singaporean identity, recognising its cultural significance beyond just food. Early efforts focused on preserving the tangible heritage of hawker centres, like their architecture and layout, as well as the intangible heritage of hawker traditions and recipes. This groundwork laid the foundation for a broader appreciation of hawker culture as a vital part of Singapore’s intangible cultural heritage. (Image Credit: National Heritage Board) |

|

| The formal push for UNESCO inscription gained momentum in the mid-2010s. Spearheaded by the NHB, the nomination process involved extensive research, documentation, and community engagement. It is also a multi-agency endeavour involving government agencies like the National Environment Agency (NEA) which is responsible for the management of hawker centres, the Federation of Merchants’ Associations Singapore, hawkers associations, community organisations, educational institutions, non-government organisations, and the Singapore population. Together, they meticulously compiled a comprehensive nomination dossier, titled “Hawker Culture in Singapore: Community Dining and Culinary Practices in a Multicultural Urban Context”, to showcase the multifaceted nature of hawker culture, from its diverse culinary offerings and unique hawkerpreneur spirit to its vital role in social cohesion and intergenerational connections. This dossier (shown above) was then submitted to UNESCO in March 2019. Click here to read it at the NHB website. (Image Credit: National Heritage Board) |

|

| In December 2020, Singapore’s hawker culture achieved international recognition when it was inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The achievement not only celebrated the unique culinary traditions of Singaporean hawkers but also acknowledged their vital role in shaping the nation’s social fabric and cultural identity. It solidified hawker culture’s place as a treasured part of Singapore’s heritage, ensuring its preservation for generations to come. (Image Credit: Photo by David Berkowitz via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)) |

A Taste of Singapore: Stories Behind Our Favourite Dishes

Singapore’s hawker food is a living story of culture, community and identity. From humble street stalls to UNESCO recognition, the video and the photo gallery below dive into how our hawker culture evolved with each generation. Hear from passionate hawkers, witness traditions in action, and discover how every dish — be it chicken rice or roti prata — carries the flavours of migration, memory and home.

Chinese Food

Singapore’s hawker centers offer an array of Chinese culinary classics. From the comforting warmth of Hainanese chicken rice, with its tender poached chicken and fragrant rice, to the smoky char kway teow, a symphony of wok hei and savory sauces, these dishes showcase the depth and diversity of Chinese culinary traditions. Here is a delicious glimpse into some common Chinese hawker food.

Malay Food

Malay cuisine in Singapore’s hawker centers offers a symphony of rich and aromatic flavors. From the fragrant coconut rice of nasi lemak, accompanied by a medley of sambal, fried chicken, and other delectable sides, to the slow-cooked, spice-infused rendang, these dishes showcase the complexity and depth of Malay culinary traditions.

Indian Food

Singapore’s hawker centers wouldn’t be complete without the vibrant and diverse flavors of Indian cuisine. From the fiery and tangy fish head curry, a beloved local favorite, to the crispy, buttery prata, perfect for dipping into flavorful curries, these dishes offer a tantalizing glimpse into India’s rich culinary heritage.

References

Click the following PDF icon to view and download the reference list used for this page: Documenting_Our_Hawkers_References